[Part 1: The phenomena surrounding interactive computing systems, Part 2: Making meaning in files, directories and automated messages]

Years ago when I was a PhD student we’d often go to the pub and debate everything all evening. Ah they were the days.

I remember one night, I was with an electrical engineer, a mechanical engineer, and then there was me, the computer scientist. The rare thing about this night was that the three of us were women. However, the argument we were having was a classic one, hingeing on whether computer science was actually a science. I said it was, they said it wasn’t, which we then managed to argue about for ages.

This memory came rushing back with great fondness yesterday, when I dug up an original document from the Association for Computing Machinery Special Interest Group on Computer-Human Interaction (ACM SIG CHI) which was written in 1992 by the Curriculum Development Group and it is a 173-page document all about how to teach HCI to university students.

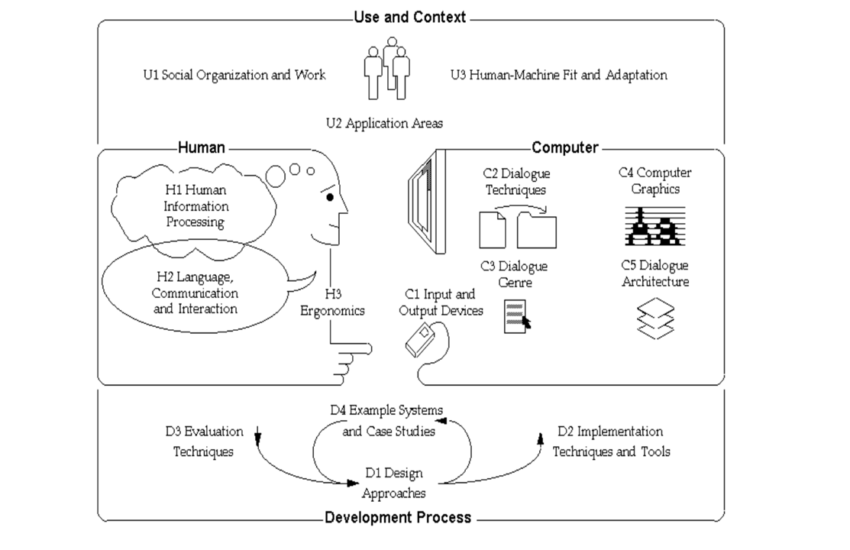

The picture at the top of this blog comes from the document and I used to use it as a roadmap when I taught HCI at Lancaster University. Today, I was looking at the document, going back to beginnings, as I was thinking about my HCI course on udemy which needs a bit of rationalisation.

The ACM SIG CHI recommendations have aged well and there’s a whole section in which they make predictions that are quite prescient, from thin displays and advances in computer graphics to how computers and television would merge. They mentioned distributed systems elsewhere in the same paper, which when all put together describes Netflix.

Interestingly, they recommend never teaching HCI as a whole degree, or as a postgraduate degree, because they insisted that HCI has to be situated within a computer science course, so as to learn how everything works within a computer. I remember going to CHI 2002 and sitting next to John Carroll and me and him talking about this. I have taught HCI to sit within a software engineering perspective, from a design perspective as John Carroll said he did too, and a multidisciplinary perspective as I taught computer science, psychology and multi-media students together.

I wonder what the Curriculum Development Group would make of the MScs in UX and in digital anthropology I guess if they could have imagined social media as it is now for everyone and anyone instead of their idea of developing: Interfaces to allow groups of people to coordinate will be common e.g., for meetings, for engineering projects, for authoring joint documents, (as the Internet was the domain of academic back then) then, they might have foreseen social media platforms, though forums and chatrooms such as compuserve were already popular. Though who could have anticipated that there’d be whole industries designing platforms and interfaces to argue with strangers, share endless cat memes, and pictures of your lunch?

Donald Norman came up with the term user experience (UX) the year after the recommendations were published, as he took up his post at Apple. And, as everyone came online, there came a shift towards product and service design, as embedded systems and websites needed to work better and sometimes in combination with each other, which has led to the Internet of Things. It is easy to see why HCI is used interchangeably with UX, separated from computer science, and used as a marketing and business term. Especially as smart companies want anything they ever design to support and further their business goals, one of which invariably is making money, closing the deal and so on. It is then a quick step into designing for persuasion and influencing the potential customer to commit if you are not careful.

However, the reason why I was put in mind of that night in the pub when we were young and carefree and there was nothing else to do apart from drink beer and split hairs, was when I saw that the major phenomena in the ACM SCI CHI definition of HCI, which is defined in the paper as:

Human-computer interaction is the design, evaluation, and implementation of interactive computing systems for human use and with the study of major phenomena surrounding them.

SIGCHI ACM (1992).

was actually repurposed from and was referring to a 1967 paper from Simon, Newell and Perlis in Science (157) 1373-4. The three of them were professors of computer science, in fact Herb Simon and Alan Newell are credited with creating the first AI system, the Logic Theorist, and Simon went on to win the Nobel Prize in Economics. Alan Perlis was the first recipient of the first Turing Prize in 1966.

In this one-page paper, they were asking (and answering) : What is computer science?

By saying:

Computer science is the study of the phenomena surrounding computers.

I hadn’t realised that it was a common argument at the time, even though I shouldn’t be surprised as everyone argued about the definition of AI for years and they still do in some quarters. They go on to say:

Wherever there are phenomena, there can be a science to describe and explain those phenomena.

Before going on to dispel the objections that people had about saying that computer science was a science, as many people believed that only a natural phenomena breed sciences. Their stance is that whilst the computers of computer science are artificial – and not a naturally occurring phenomena like the Aurora Borealis, a murmuration of birds, or the movement of the stars and planets – the algorithms should be viewed as living. They change and grow as humans recreate them to solve ever more complex problems, to say nothing of the way that people respond to computers and change their behaviour accordingly. And, this is a phenomena in and of itself. Computer science – the study of computers – becomes a science.

This too is prescient, especially now as many scientists use AI. We just have to look at how Google’s Alphafold found a protein folding solution that had not been possible for over 50 years which led to a Nobel Prize in Chemistry. A friend of mine noted how now scientists will be forever chasing and proving the accuracy of AI discoveries, instead of observing natural phenomena.

I wish I had already read the What is computer science? paper that night in the pub, though I doubt it would have changed much. My mates were very much working from the original sciences, though interestingly they included mathematics. My mates’ argument was that computer science was the application of mathematics, and a poor relative. Maths though was, for them, included in the natural sciences, so it got the thumbs up. I have always viewed computer science as coming from natural philosophy, rather like AI, which for me is a subset of computer science, because we debate what is mind, what is intelligence etc., and we are trying to replicate things humans do in a computer, or at the very least augment what humans do with a computer. Natural philosophy is the precursor to the natural sciences, so there we are. Computer science a science. Not that it mattered that night in the pub, they weren’t having it and I didn’t explain my reasoning very well so was happy enough to give up so that I could slurp my beer and listen to what they said. Though I love how even back in 1967, Simon, Newell and Perlis recognised the place of computers in society:

Computer scientists will often join hands with colleagues from other disciplines in common endeavour. Mostly, computer scientists will study living computers with the same passion that others have studied plants, stars, glaciers, dyestuffs, and magnetism; and with the same confidence that intelligent, persistent curiosity will yield interesting and perhaps useful knowledge.

Simon, Newell and Perlis, Science (157) 1373-4.

Here I am many years later totally agreeing about that. In the same way that I have thought about HCI and how it remains really important. HCI is in every part of society and yet is still treated like the poor relative of computer science. I had a couple of old crusty profs through the years tell me that it is not a proper subject, just handwaving, rather like those people who said computer science wasn’t a subject either, because it was new, they couldn’t understand its contribution.

As humans increase their collaboration/codependency with/on computers, the phenomena around interactive systems, and those not so interactive ones of which AI is currently a fan (I’m looking at you, ChatGPT) will only increase. We don’t really want to unravel the tangle of terrible IT systems we have invested time and money into, we would rather throw more money at it by spending money on AI and hoping it will sort it all out instead.

I was at a meeting the other day and someone categorically stated that getting two specific software systems interfacing together cannot be done. People have tried. I mean really? Shame on the IT department for not licencing better software suitable to their user needs. Instead they are going to add new layers over the top and cross their fingers and hope for the best.

They are not alone, everyone will do this, it is a common phenomena in computer science, until we as a society finally understand that to use AI and any other computer system effectively, we must take responsibility for our actions. We must design excellent software architecture that maps right onto the HCI so that people especially, highly trained scientists, understand exactly what it is doing, as it is doing it, so that they can collaborate effectively and not become merely the computers of AI.