Recently, Rebecca Solnit in The Guardian described the year 1995, as that old, slow world you could describe the way George Eliot described life before the railroad.

Solnit goes on to describe her stately 1995 routine: She read the newspaper in the morning, listened to the news in the evening and received other news via letter once a day. Her computer was unconnected and so, behaved like a word processor on a desk.

Nowadays, her computer is more like a cocktail party full of chatter increasingly fragmented streams of news and data, leaving Solnit to feel like an anachronism in this completely different world.

As a computer scientist in 1995, my experience was quite different. I already had my first webpage: ‘Hello World!’ and felt connected. I was a graphics programmer and HCI researcher, and I loved sharing information on newsgroups or by email. I lived in Switzerland and was thrilled when the UK newspapers went online. I no longer had to wait for day old news from good old Blighty. Technology helped my research and enriched my life daily.

Ten years on, I trained to be a journalist. During the course, we were told to read all the newspapers everyday and then pitch articles which were very similar to the ones already in the paper. Anniversaries of public events and the deaths, marriages of famous people, were always good fodder to fill up the papers. And a spot of ambulance chasing could get you that human interest story.

It did strike me as all a bit old-fashioned. So, I shouldn’t be so surprised that Solnit feels left behind. This new technology is threatening her way of life when really it could be helping her. And it is interesting that Solnit compares the rate of change today with the Victorian railroads and the fast changing world back then. It is a satisfying comparison.

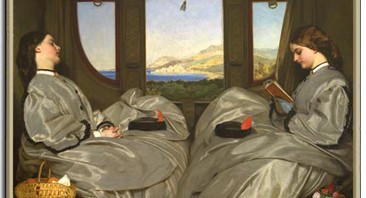

Alison Byerly, in her book, Are we there yet? Virtual travel and Victorian realism recently reviewed in the TLS, compares chat rooms to railway carriages, SimCity to hot air balloons, and blog links to K. Jerome’s Three Men in a Boat. She also gives a lovely example of Victorian armchair travel when she describes Albert Smith’s Ascent of Mont Blanc (1851-6), which was an interactive scene of a full scale chalet exterior, a pool of water containing live fish, and ten Saint Bernards who would trot about the auditorium delivering packets to chocolate to children. Smith targeted people who would never actually go to Mont Blanc. It was too far and too expensive to travel in their lifetimes. But they could go along to his exhibition and experience the thrill of the ascent.

Today, with a click of a button, we can watch footage of people climbing Mont Blanc and eating chocolate on YouTube. Byerly mentions virtual reality (VR) as another parallel for Smith’s exhibition: but really how many people do you know have a head-mounted display and data-gloves? And really is VR what we need? After, it is a shared experience we are seeking, something we can talk about and take part in together in order to understand. Elsewhere in her book, Byerly gives examples of Victorian full-scale recreations of train crashes and other disasters.

Recently, the New York Times ran a long feature called Snow Fall online about an avalanche at Tunnel Creak, Stevens pass, Washington. There are slide shows of the deceased and their families, pictures of the history of Tunnel Pass, and a computer-generated simulation of the avalanche. It is a great piece of journalism enriched beautifully by technology. It is the modern day equivalent of the Victorian exhibitions.

According to Wikipedia, journalism began in 1400s. Italian and German businessmen wrote down the latest news and circulated it to their connections in the city. The practice grew, especially during wartime so that the people back home would know what was going on. Journalists were providing a service – informing and updating peoples’ lives.

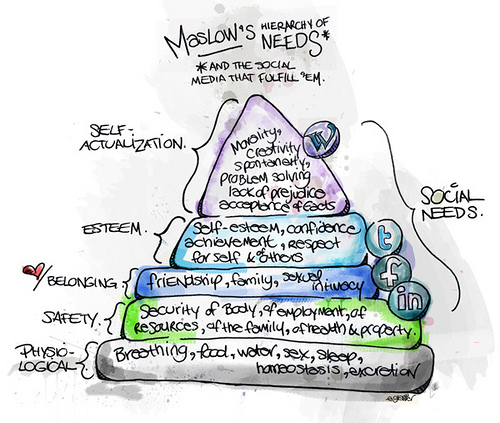

And, now we have access to the latest news all the time. From the simple #hashtag on twitter to longer news articles which are presented in a magazine format by Flipboard. But it is not always new information that we need. Sometimes, we need in depth analysis and explanation, a shared experience, a shared understanding.

At best, journalists are recorders of our time. They bring us life changing historical events, perceived injustices, and remind us of things we should never forget. They write it down and revisit so that we don’t forget. Good journalists articulate our thoughts and connect to our minds. Now they can do this better than ever with insightful visualisation whilst connecting information to give us insight and enlightenment.

Magazine mogul, Chris Anderson, started the TED talks because he felt that television wasn’t challenging enough and he believed intellectual mobility was the future. In an article in the Guardian, Anderson talks about crowd-accelerated learning, and bringing intellectual stimulus and experience to YouTube audiences by the world’s leading thinkers.

The positive adoption of technology by broadcast media and TV networks (like OWN) and some journalists is exciting. Many broadcast and media courses now teach emerging technologies and so the potential is there to create enriching and enlightening features that educate us all.

Emerging journalism: a new way of sharing experiences.

Would love to go to Switzerland but have experienced it though Harper’s White Spider and Frankenstein of course.

Brilliant though I am surprised you haven’t run or cycled right round it yet, ‘cos you are impressively fit!