I’ve learned that people will forget what you said, people will forget what you did, but people will never forget how you made them feel

– Maya Angelou

[ Part 3 of 5: 1) The intimacy of the written word, 2) Structure, 3) Archetypes and aesthetics, 4) Women 5) Possession, the relations between minds]

I used to believe that my time was the most precious commodity that I had to give to someone else. Now, I know it is the energy that I bring with me.

Our energy is what stays with other people long after we have left and vice-versa. You never forget how people made you feel, and even if you never see them again, the very thought of them can enrich or deplete you.

Archetypes can do the same in any given story. They bring energy based on the story patterns we know from when us humans first started telling stories. They are ritualistic and encourage the reader to infuse the narrative with their own emotions. Archetypes can arouse fears and anxieties or yearnings and desires.

The field of archetypal literary criticism looks at how all narratives have intertextual elements. This means that we recognise story patterns and symbolic associations from other texts. For example, we know what a black pointy hat signifies. We know a night time setting is quite different from day time. We have learnt this from all the others stories we have read prior to the one we are reading now. Meaning does not exist independently.

They broke the mould when they made you

In design, archetypes are the first examples of their type, and may be reused to inspire a new design but they are never just copied. And, so it is the same in storytelling. We don’t want the same character but we want the new character to be moulded in a similar way as the original. The Greek word archetupos means first-moulded, which probably inspired the idiomatic, yet delightful, compliment: They broke the mould when they made you.

Archetypes are not just characters but can be settings such as caves, mazes, deserts, mountains, etc. Each one suggests certain ritual experiences such as the discovery of self (cave), spiritual quests (maze or mountain), or spiritual wastelands (desert). Each setting brings a certain energy which primes our expectations and how to respond. Archetypes can also be events: birth, death, first love, leaving home, those rites of passage which define our lives.

Common patterns and ways of living

It was Carl Jung who first suggested that as these common patterns and ways of living have emerged in many cultures, they are hardwired in our brains and they lead to us being predisposed to think a certain way about them, even unconsciously.

Jung worked on his theory of archetypes for many years often without pinning down exactly what he meant. Though finally, he compared the form of the archetype to the lattice of a crystal which dictates the crystal’s shape and matter, even though it has no material existence of its own, rather like the form follows function principle in design where something is pared down, is beautiful, and develops organically.

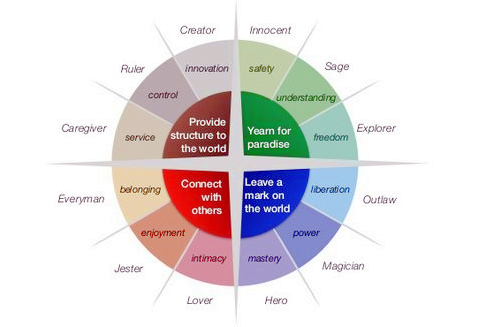

Today, it is common to refer to a specific number of archetypes like the 12 in the image above. Variations of this image are used in marketing, as marketers like to tap into stories already known in order to make their products seem familiar, which they then wrap up in beautiful aesthetics because research has shown that art rewards us. It lights up our reward centre in our brain.

Archetype + aesthetic = irresistible

A familiar archetype wrapped in lovely packaging – known as the art infusion effect – is irresistible. We want to consume shiny new things, and if they seem a little familiar and they resonate, what could be better?

I like the above diagram because it has echoes of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs and we can put the four groups of archetypes alongside the five groups of needs (plus the extra transcendance needs Maslow later added to his pyramid) like so:

- Physiological and Safety needs = Provide structure to the world.

- Social needs = Connect with others.

- Esteem needs = Leave a mark on the world.

- Self-actualization and transcendence needs = Yearn for paradise.

I first realised that our needs and motivations haven’t changed since the Iron Age when I visited a Crannog one summer. We may look like we are doing things differently, but we still need to feel warm and fed, loved and connected, esteemed and self-actualised, which then begs the question: How much have our stories changed through time when our needs haven’t?

Motifs, symbols and facets

Scriptwriter Christopher Vogel uses seven archetypes because he has based his on the hero’s journey or monomyth which was first identified by mythologist Joseph Campbell.

Inspired by Soviet folklorist Vladimir Propp’s 31 story functions and seven character functions, which are used in the study of semiotics, Vogel says that the archetypes in a good story function like motifs or symbols, or as a facet of the main character’s personality. Propp himself said that they were like the masks we adopt in life to fit in, to protect ourselves, to not be vulnerable, until finally we become that version of who we think others want us to be, and we forget who we really are.

The seven archetypes are often used in psychotherapy. The theory is that if we know what archetypes we have adopted and how they make up our thought patterns and beliefs in our mind, then we can work with them to stop limiting beliefs and engage in personal growth.

Seven archetypes for storytelling

- The hero is the one with whom the audience identifies, and includes growth, action, and sacrifice. The hero represents Freud’s ego and our search for identity and wholeness.

- The mentor stands for our highest aspirations or higher self, a teacher or a gift giver. The mentor is our conscience and a plot device which plants information. There are also dark mentors who mislead us.

- The shapeshifter is the one who brings doubt and suspense into a story. It may be a lover who is close and loving but turns out to betray us.

- The threshold guardian represents our barriers or neuroses, they test us and a successful hero learns that threshold guardians are useful allies.

- The trickster is the one who cuts us down to size, teaches us humility, and bring about healthy change and transformation. The trickster also provides comic relief, thus releasing tension and making us laugh at ourselves in order to create change.

- The shadow can represent suppressed emotions such as a hero damaged by doubt. The shadow may be external who challenges the hero and gives them a worthy opponent. They may even be a love interest – someone who is bad for us, who doesn’t have our best interests at heart. Sometimes, the shadow represents feelings such as anger, which is a healthy emotion until it is suppressed, turned inward, and can lead to depression.

- The herald brings words of challenges, to signal change to move the plot on whenever they are needed.

How do we feel when we meet these archetypes in the characters, in our familiar story-structures, in the spaces that writers create? Do we feel the energy they have to impart? Does it suppress or empower us? Delight or dismay us? We enter into that shared heart space and we come out the other end a little different to when we went in, carrying a new energy that we got to keep. Storytelling, the most powerful way to communicate ever.

12 comments